Editioning Fine Art Prints

I’m a printmaker. I love printmaking. And I call myself an artist (it took me a number of years to build up the courage to say that out loud let alone type it for the world to read!). I produce hand printed fine art limited edition prints in a range of different printmaking mediums.

It’s frustrating that there is still confusion around the difference between fine art prints and reproduction prints. Michelle Perry wrote a great post on the Australian Printmakers page about this topic – https://www.facebook.com/groups/166753066675130/permalink/1359824994034592/

But … my dilemma has been knowing how to number and edition my prints. I caught up with an artist friend a few days ago and she introduced me to a new term – “Hors de Commerce” – thank you Fiona Dempster!

So I did some research and found whole set of editioning definitions and have come up with my own numbering systems. I’m sure there are more terms, and I’ll add them as I come across them.

Hors de Commerce – HC

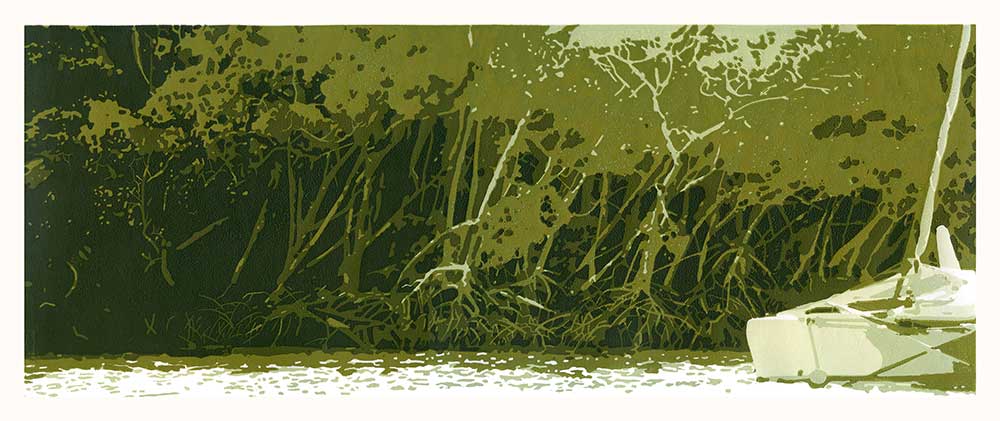

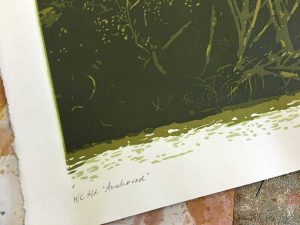

This new discovery has changed how I number what I had considered to be Artist Proofs. Prints annotated HC (Hors de Commerce) are “not for sale”. These “proofs” started to appear as extensions of editions being printed in the late 1960s. They may differ from the edition by being printed on a different paper or with a variant inking; they may also not differ at all. Publishers may sometimes use such impressions as exhibition copies, thereby preserving the numbered impressions from rough usage. I will use this annotation to number prints that I feel are less-than-prefect for a the final edition or exhibition and used as an artist’s trade, but what I consider still a valid impression. Now I know how to annotate my print “overs” that I didn’t feel quite fit with the final limited edition.

This new discovery has changed how I number what I had considered to be Artist Proofs. Prints annotated HC (Hors de Commerce) are “not for sale”. These “proofs” started to appear as extensions of editions being printed in the late 1960s. They may differ from the edition by being printed on a different paper or with a variant inking; they may also not differ at all. Publishers may sometimes use such impressions as exhibition copies, thereby preserving the numbered impressions from rough usage. I will use this annotation to number prints that I feel are less-than-prefect for a the final edition or exhibition and used as an artist’s trade, but what I consider still a valid impression. Now I know how to annotate my print “overs” that I didn’t feel quite fit with the final limited edition.

If I were to annotate an Hors de Commerce proof, I would use “HC 1/X” where X is the total number of Hors de Commerce Proofs.

Artist Proof – AP

I love and collect Artist Proofs. Way back when, when an artist was commissioned to execute a print, they were given with accommodation and living expenses, a printing studio and workmen, supplies and paper. The artist was given a portion of the edition (to sell) as payment for his work – these were the Artist Proofs.

I have always approached Artist Proofs and my initial prints getting the colours and image to my own expectation, therefore they were often the 1st and 2nd pull from the press, less than perfect when compared to the final edition, but with their own unique character.

However, I didn’t realise that by today’s standards they are named such to denote a certain number of impressions put aside for the artist to do with as they will.

If I were to annotate an Artist proof, I would use “AP 1/X” where X is the total number of Artist Proofs.

They can also be numbered Epreuve d’artiste or EA.

The number of Artist proofs should not exceed 10% of the total number of the edition.

Trial Proof – TP

A working proof pulled before the edition to see what the print looks like at a stage of development, which differs from the edition. There can be any number of trial proofs, but usually it is a small number and each one differs from the others.

If I were to annotate a Trial proof, I would use “TP 1/X” where X is the total number of Trial Proofs.

Bon a Tirer Proof – BAT

Literally, the “okay-to-print” proof. If the artist is not printing his own edition, the bon a tirer is the final trial proof, the one that the artist has approved, telling the printer that this is the way he wants the edition to look. There is only one of these proofs for an edition and can be accompanied by printing notes (paper, ink or inking process) to be used as a reference for the printing of the whole edition.

Hmmm. Not sure I will have an occasion to use this annotation system. But if I did… I would use “b.a.t.” where X is the total number of Bon a Tirer Proofs.

Printers Proof – PP

A complimentary copy of the print given to the publisher. There can be from one to several of these proofs, depending on how many printers were involved in the production of the print.

If I were to annotate a Printers proof, I would use “PP 1/X” where X is the total number of Printers Proofs.

Numbering & Editioning

Numbering printed editions didn’t start until the late nineteenth century. However, it wasn’t a standard practice until the mid 1960s. Today, all limited edition prints should be numbered, with the first number being the impression number and the second number representing the whole edition. For example 3/10, where 3 is the 3rd impressions from and edition of 10 prints.

The numbering sequence does not necessarily reflect the order of printing; prints are not numbered as they come off the press but some time later, after the ink has dried.

The edition number does not include proofs (as noted above), but only the total in the numbered edition.

When I annotate an editioned print, I use “1/X” where X is the total number of impressions for that edition.

Edition Variable – EV

You can have fun with this. With an EV print, the impression may be printed then hand coloured, or printed onto different papers, or combined with a Chine collé collaged through the press.

If I were to annotate an Edition Variable print, I would use “EV 1/X” where X is the total number of impressions in the edition.

Open Edition – O

If you want to print an image, but it is not to be a Limited Edition, but rather an impression from a plate that you intend to print multiple times, you can annotate it as an Open Edition.

If I were to annotate an Open Edition print, I would use “O 1”, where the number is the number printed to date foe the open edition, but with no need for the total edition number . ie “/X”.

And combine that with an Open Edition and you get OEV “OEV 1”

Signatures

Very early prints were not signed. In the later part of the fifteenth century many artists “signed” their prints by incorporating a signature or monogram into the design as “signed in the plate” or “plate signature.” While some prints were pencil signed as early as the late eighteenth century, the practice of signing work in pencil or ink did not become common practice until the late 1880’s, probably coinciding with the practice of numbering editions. Signing a print as initially done for the benefit of collectors; artists and publishers, when presented with a choice, preferred to buy pencil-signed impressions rather than an unsigned print. Today it is expected that original prints to be signed by the artist, and an unsigned impression of the same print is generally not as commercially valuable.

Article sources:

- www.monoprints.com

- www.printshop.org/glossary

Great article, thank you for sharing this information.

Hi Jody, you are so very welcome. Thank you for reading. cheers, Kim