There’s More to John Herschel Than Cyanotype

I have a deep affection for cyanotype – that beautiful blue, alternative photographic process that has become an integral part of my creative work. Invented in 1842 by Sir John Herschel (1792-1871), cyanotype is one of the earliest photographic printing techniques, using sunlight and iron salts to create images that result in that distinctive Prussian blue.

But cyanotype was only one part of Herschel’s legacy. I knew he was an astronomer and a scientist, but I didn’t know much more than that. I had thought he was credited with discovering Uranus, but it was his father, William Herschel (1739-1822).

I was recently watching Wonders of the Solar System with Professor Brian Cox. I was excited to hear Herschel’s name come up … not in relation to photography, but as a scientist who made some very significant contributions to our understanding of the universe. It made me realise just how much more there is to appreciate about this remarkable figure. And it sent me down a rabbit-hole of online searching and reading.

A Bit of Cyanotype History

Herschel discovered the cyanotype process while experimenting with light-sensitive iron salts. He was searching for ways to make photographic copies of his notes – essentially inventing what we call the “blueprint”. Cyanotype never really caught on for portraiture or popular photography, but it found practical use in technical drawing reproduction.

Then, enter Anna Atkins (1799-1871). A botanist and family friend of Herschel, Atkins used cyanotype to self-publish what is considered to be the world’s first photographic reference book: Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1843). Her delicate plant impressions elevated the cyanotype process from a practical tool to a valuable artform.

John Herschel gave us the chemistry. Anna Atkins gave us the beauty.

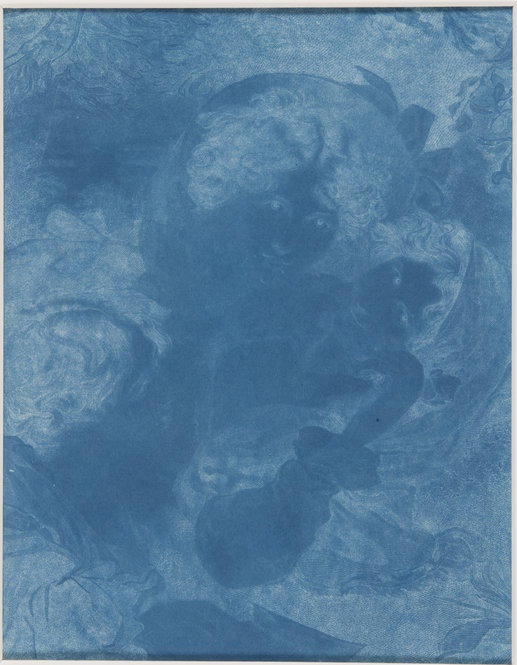

- “A Scene in Italy”. Henry Cook Engraving 1839

- “A Scene in Italy”. John Herschel cyanotype made from Henry Cook’s Engraving 1839

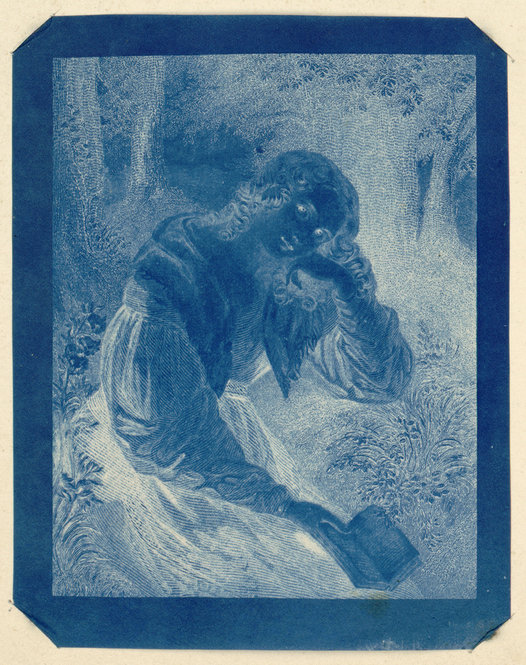

- “Still in my Teens”. John Herschel cyanotype 1838

Herschel’s Other Discoveries

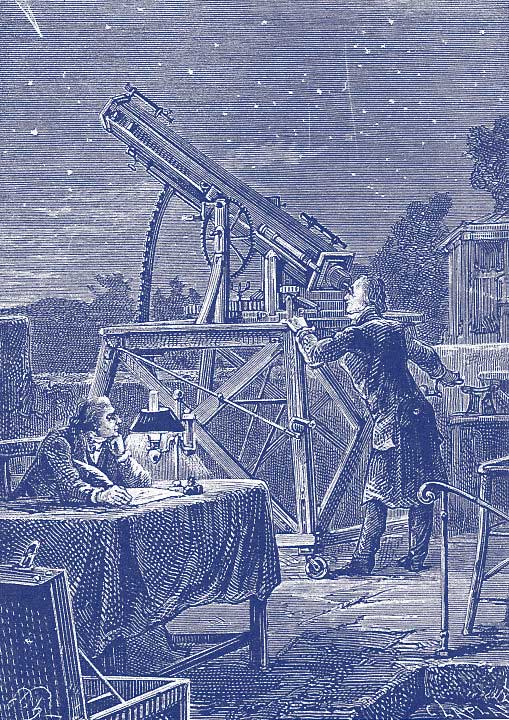

An illustration to Jules Verne’s novel Hector Servadac from 1877 shows Herschel observing Halley’s Comet in 1835 in Cape Town. Engraving by Charles Laplante after Paul Philippoteaux. Source Wikipedia.org

He mapped the Southern Skies

In the 1830s, Herschel set up an observatory in Cape Town, South Africa, where he catalogued thousands of stars and nebulae, and galaxies visible from the southern hemisphere. Exactly how many I’ve not been able to determine, but I found sources ranging from 68000 to 170000. Regardless, his work helped complete the sky surveys begun by his father, William Herschel, and provided the first comprehensive view of the southern celestial hemisphere.

He coined the terms “Positive” and “Negative” in photography

Before cyanotype, Herschel was already making waves in photography. He coined many of the terms we still use today in image-making, including the word “photography” itself! He introduced the words “positive” and “negative” to describe photographic images, laying the linguistic foundations of the medium.

He helped uncover the nature of the Sun’s orbit

Herschel conducted pioneering work on the motion of the solar system, using star catalogues to demonstrate that our Sun moves through space in a specific direction, toward what’s now called the “solar apex.”

Oh dear! Another rabbit-hole … what is “solar apex”? I had to look that up. According to Merriam-Webster, “solar apex” is a point of the celestial sphere lying in the constellation Hercules toward which the sun and the solar system are moving with respect to the stars in the solar neighborhood at a rate of about 12 miles per second.

He calculated the Sun’s energy output

Using nothing more than a cup of water, a thermometer and a black umbrella, Herschel calculated one of the first rough estimates of solar radiation received on Earth. He placed a cup of water under direct sunlight and measured how quickly the temperature rose, using a blackened background to absorb more sunlight (the umbrella helped shade surrounding areas and reduce reflected light). From this, he calculated the heat energy being transferred and extrapolated it to estimate the total energy the Sun emits. His figure wasn’t accurate by modern standards, but the method was revolutionary at the time, and surprisingly close using the simple tools of his time.

It was this energy calculation that Brian Cox spoke about in his documentary, then motivating me to write this post.

More Than “Just” Blueprints

I adore cyanotype. It is simple, beautiful and chemically magical. But it’s only one small piece of Herschel’s genius. His contributions spanned astronomy, chemistry, physics and photography. He left an enduring mark on both science and the arts, and I think he deserves to be remembered for the full breadth of his curiosity and vision.

I make a strong point of talking about Anna Atkins in my Cyanotype workshops. Talking about her contribution to the craft and art of cyanotype, and the fact that she was a woman living in Victorian England and created the world’s first botanical reference book.

Next time you lay a fern on cyanotype-coated paper and set it out in the sun, take a moment to think about the man behind the process. Then think about the woman who elevated the process to a relevant art form. They weren’t just giving us blueprints and book pages – they were helping us see the world, and the universe, in entirely new ways.